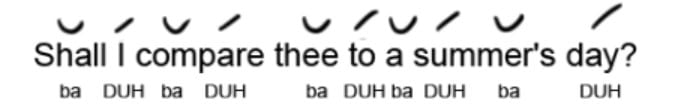

In the example below, one of Shakespeare’s most famous sonnets, he collapses several words with apostrophes so they fit within the requisite number of ten syllables per line: the two syllables of owest down one for ow’st, the three syllables of wanderest down to two for wand’rest, and the two syllables of growest down one for grow’st. Iambic pentameter also de-emphasizes the rhyme at the end of each line, since it falls on one of the regularly accented syllables, therefore giving it no more weight in the line than any of the other accented syllables. This allowed the flow of each line of poetry to seem as familiar as possible to both readers and listeners. Writers in Shakespeare’s era believed that iambic pentameter most closely matched the normal speaking patterns of native English speakers. Each line is written in iambic pentameter, meaning that each lines contains exactly ten syllables, every other one accented.

Shakespearean sonnets end in two lines that rhyme with one another, called a couplet. Shakespeare also followed another rule that was popular during his era but far less now. Sonnets typically have ten beats in a line this is called an iambic pentameter.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)